Manufacturing Desire

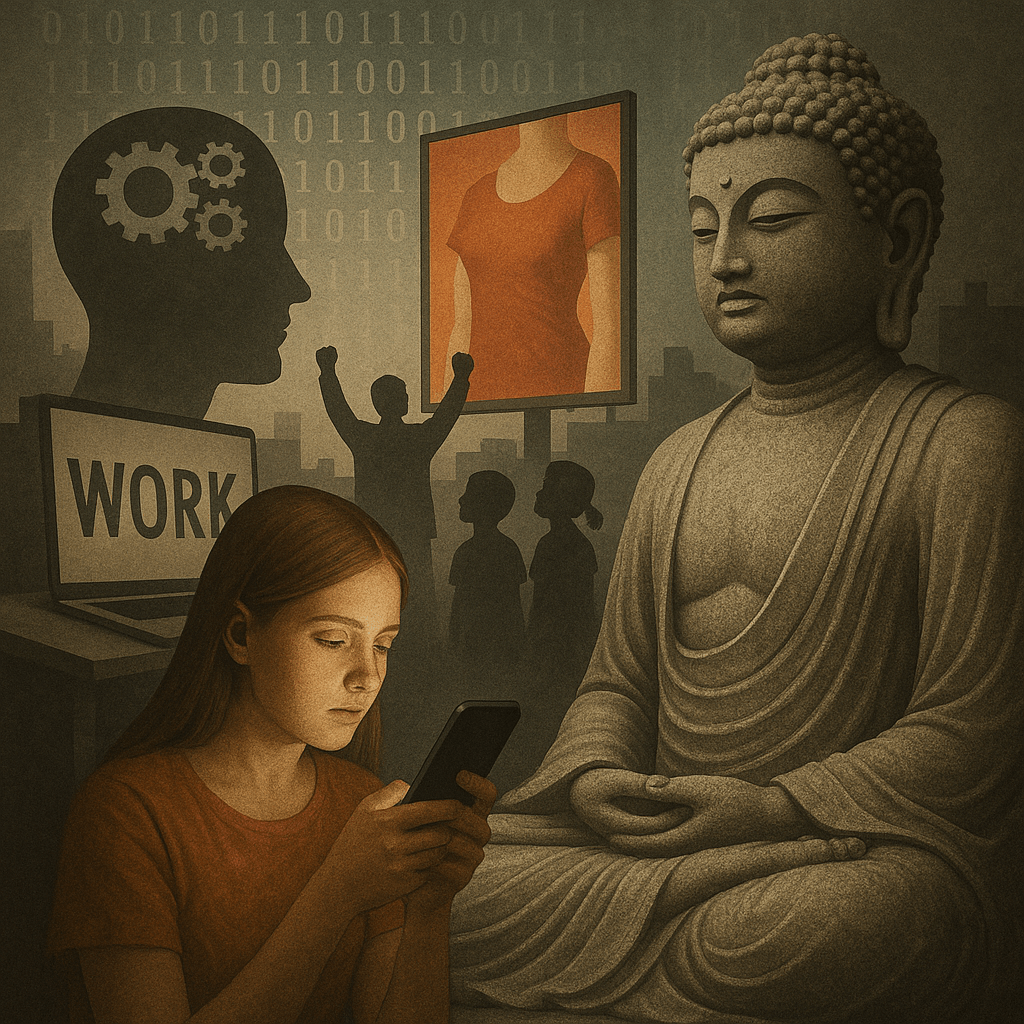

In an era when technological progress promises freedom and efficiency, many find themselves paradoxically more burdened, less satisfied, and increasingly detached from meaningful work and community. The rise of artificial intelligence and digital optimisation has revolutionised industries and redefined productivity—but not without cost. Beneath the surface lies a complex matrix of invisible control, user profiling, psychological manipulation, and systemic contradictions. Drawing from anthropologists, historians, and data scientists, this post explores how behaviour modification, corporate surveillance, and the proliferation of “bullshit jobs” collectively undermine our autonomy, well-being, and connection to the natural world.

Originally published in Substack https://substack.com/home/post/p-164145621

Manipulation of Desire

Large language models, or AI tools, are designed to optimise production by quantifying employees’ contributions relative to overall output and costs. This logic, however, rarely applies to upper management—those who oversee the operation of these very systems. Anthropologist David Graeber (2018) emphasised that administrative roles have exploded since the late 20th century, especially in institutions like universities where hierarchical roles were once minimal. He noted that science fiction authors can envision robots replacing sports journalists or sociologists, but never the upper-tier roles that uphold the basic functions of capitalism.

In today’s economy, these “basic functions” involve finding the most efficient way to allocate available resources to meet present or future consumer demand—a task Graeber argues could be performed by computers. He contends that the Soviet economy faltered not because of its structure, but because it collapsed before the era of powerful computational coordination. Ironically, even in our data-rich age, not even science fiction dares to imagine an algorithm that replaces executives.

Ironically, the power of computers is not being used to streamline economies for collective benefit, but rather to refine the art of influencing individual behaviour. Instead of coordinating production or replacing bureaucracies, these tools have been repurposed for something far more insidious: shaping human desires, decisions, and actions. From Buddhist perspective manipulation of human desire sounds dangerous. The Buddha said that the cause or suffering and dissatisfaction is tanha, which is usually translates as desire or craving. If human desires or thirst is manipulated and controlled, we can be sure that suffering will not end if we rely on surveillance capitalism. To understand how we arrived at this point, we must revisit the historical roots of behaviour modification and the psychological tools developed in times of geopolitical crisis.

The roots of modern Behaviour modification trace back to mid-20th-century geopolitical conflicts and psychological experimentation. During the Korean War, alarming reports emerged about American prisoners of war allegedly being “brainwashed” by their captors. These fears catalysed the CIA’s MKUltra program—covert mind control experiments carried out at institutions like Harvard, often without subjects’ consent.

Simultaneously, B.F. Skinner’s Behaviourist theories gained traction. Skinner argued that human behaviour could be shaped through reinforcement, laying the groundwork for widespread interest in behaviour modification. Although figures like Noam Chomsky would later challenge Skinner’s reductionist model, the seed had been planted.

What was once a domain of authoritarian concern is now the terrain of corporate power. In the 21st century, the private sector—particularly tech giants—has perfected the tools of psychological manipulation. Surveillance capitalism, a term coined by Harvard professor Shoshana Zuboff, describes how companies now collect and exploit vast quantities of personal data to subtly influence consumer behaviour. It is very possible your local super market is gathering date of your purchases and building a detailed user profile, which in turn is sold to their collaborators. These practices—once feared as mechanisms of totalitarian control—are now normalised as personalised marketing. Yet, the core objective remains the same: predict and control human action – and turning that into profit.

Advertising, Children, and the Logic of Exploitation

In the market economy, advertising reigns supreme. It functions as the central nervous system of consumption, seeking out every vulnerability, every secret desire. Jeff Hammerbacher, a data scientist and early Facebook engineer, resigned in disillusionment after realising that some of the smartest minds of his generation were being deployed to optimise ad clicks rather than solve pressing human problems.

Today’s advertising targets children. Their impulsivity and emotional responsiveness make them ideal consumers—and they serve as conduits to their parents’ wallets. Meanwhile, parents, driven by guilt and affection, respond to these emotional cues with purchases, reinforcing a cycle that ties family dynamics to market strategies.

Devices meant to liberate us—smartphones, microwave ovens, robotic vacuum cleaners—have in reality deepened our dependence on the very system that demands we work harder to afford them. Graeber (2018) terms the work that sustains this cycle “bullshit jobs”: roles that exist not out of necessity, but to perpetuate economic structures. These jobs are often mentally exhausting, seemingly pointless, and maintained only out of fear of financial instability.

Such jobs typically require a university degree or social capital and are prevalent at managerial or administrative levels. They differ from “shit jobs,” which are low-paid but societally essential. Bullshit jobs include roles like receptionists employed to project prestige, compliance officers producing paperwork no one reads, and middle managers who invent tasks to justify their existence.

Historian Rutger Bregman (2014) observes that medieval peasants, toiling in the fields, dreamt of a world of leisure and abundance. By many metrics, we have achieved this vision—yet rather than rest, we are consumed by dissatisfaction. Market logic now exploits our insecurities, constantly inventing new desires that hollow out our wallets and our sense of self.

Ecophilosopher Joanna Macy and Dr. Chris Johnstone (2012) give a telling example from Fiji, where eating disorders like bulimia were unknown before the arrival of television in 1995. Within three years, 11% of girls suffered from it. Media does not simply reflect society—it reshapes it, often violently. Advertisements now exist to make us feel inadequate. Only by internalising the belief that we are ugly, fat, or unworthy can the machine continue selling us its artificial solutions.

The Myth of the Self-Made Individual

Western individualism glorifies self-sufficiency, ignoring the fundamental truth that humans are inherently social and ecologically embedded. From birth, we depend on others. As we age, our development hinges on communal education and support.

Moreover, we depend on the natural world: clean air, water, nutrients, and shelter. Indigenous cultures like the Iroquois/Haudenosaunee express gratitude to crops, wind, and sun. They understand what modern society forgets—that survival is not guaranteed, and that gratitude is a form of moral reciprocity.

In Kalahari, the San people question whether they have the right to take an animal’s life for food, especially when its species nears extinction. In contrast, American officials once proposed exterminating prairie dogs on Navajo/Diné land to protect grazing areas. The Navajo elders objected: “If you kill all the prairie dogs, there will be no one to cry for the rain.” The result? The ecosystem collapsed—desertification followed. Nature’s interconnectedness, ignored by policymakers, proved devastatingly real.

Macy and Johnstone argue that the public is dangerously unaware of the scale of ecological and climate crises. Media corporations, reliant on advertising, have little incentive to tell uncomfortable truths. In the U.S., for example, television is designed not to inform, but to retain viewers between ads. News broadcasts instil fear, only to follow up with advertisements for insurance—offering safety in a world made to feel increasingly dangerous.

Unlike in Finland or other nations with public broadcasters, American media is profit-driven and detached from public interest. The result is a population bombarded with fear, yet denied the structural support—like healthcare or education—that would alleviate the very anxieties media stokes.

Conclusions

The story of modern capitalism is not just one of freedom, but also of entrapment—psychological, economic, and ecological. Surveillance capitalism has privatised control, bullshit jobs sap our energy, and advertising hijacks our insecurities. Yet throughout this dark web, there remain glimmers of alternative wisdom: indigenous respect for the earth, critiques from anthropologists, and growing awareness of the need for systemic change.

The challenge ahead lies not in refining the algorithms, but in reclaiming the meaning and interdependence lost to them. A liveable future demands more than innovation; it requires imagination, gratitude, and a willingness to dismantle the myths we’ve mistaken for progress.

References

Bregman, R. (2014). Utopia for realists: And how we can get there. Bloomsbury Publishing.

Eisenstein, C. (2018). Climate: A new story. North Atlantic Books.

Graeber, D. (2018). Bullshit Jobs: A Theory. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Hammerbacher, J. (n.d.). As cited in interviews on ethical technology, 2013–2016.

Johnstone, C., & Macy, J. (2012). Active hope: How to face the mess we’re in without going crazy. New World Library.

Loy, D. R. (2019). Ecodharma: Buddhist Teachings for the Ecological Crisis. New York: Wisdom Publications.

Skinner, B. F. (1953). Science and human Behaviour. Macmillan.

Zuboff, S. (2019). The age of surveillance capitalism: The fight for a human future at the new frontier of power. London: PublicAffairs.

Chomsky, N. (1959). A review of B. F. Skinner’s Verbal Behaviour. Language, 35(1), 26–58.