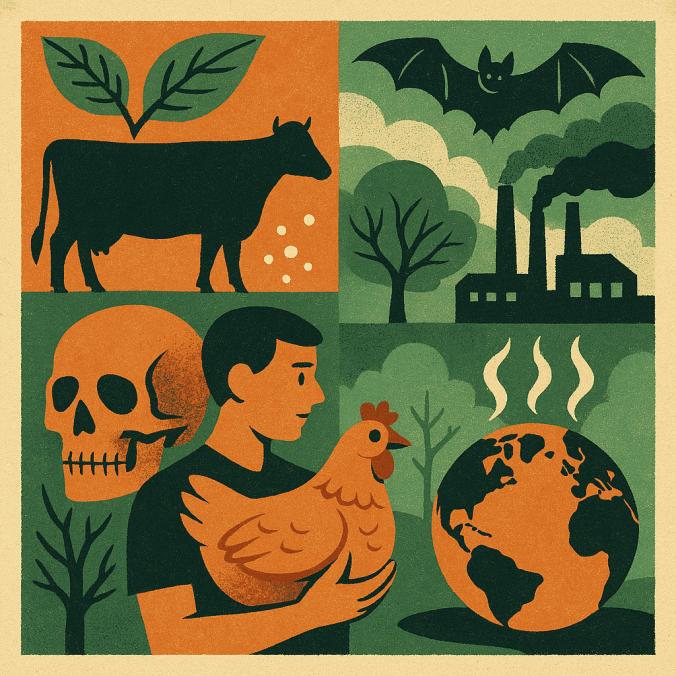

Pandora’s Livestock: How Animal Agriculture Threatens Our Planet and Our Health

The following post explores the interconnected crises of biodiversity loss, industrial animal agriculture, and climate change, presenting a comprehensive argument about humanity’s complex role in environmental degradation. Drawing from works by Bill Gates, Risto Isomäki, and others, the text combines ecological science, epidemiology, and cultural history to examine both systemic failures and potential paths forward. The post highlights how deeply entangled environmental destruction, pandemics, and human psychology are — while also questioning whether our current cognitive limits allow us to grasp and act upon such intertwined threats.

Originally published in Substack: https://substack.com/home/post/p-166887887

The destruction of ecological diversity, the shrinking habitats of wild animals, and the rise of industrial livestock production represent grave violations against the richness of life — and profound threats to humanity’s own future. These issues go beyond climate change, which is itself just one of many interconnected problems facing nature today.

The Decline of Biodiversity and the Rise of Climate Complexity

In How to Avoid a Climate Disaster (2021), Bill Gates outlines the sources of human-generated greenhouse gas emissions. Although many factors contribute to climate change, carbon dioxide (CO₂) remains the dominant greenhouse gas emitted by humans. Gates also includes emissions of methane, nitrous oxide, and fluorinated gases (F-gases) in his calculations. According to his book, the total annual global emissions amount to 46.2 billion tons of CO₂-equivalent.

These emissions are categorized by sector:

- Manufacturing (cement, steel, plastics): 31%

- Electricity generation: 27%

- Agriculture (plants and animals): 19%

- Transportation (planes, cars, trucks, ships): 16%

- Heating and cooling: 7%

This classification is more reader-friendly than the Our World In Data approach, which aggregates emissions into broader categories like ”energy,” comprising 73.2% of total emissions. Agriculture accounts for 18.4%, waste for 3.2%, and industrial processes for 5.2%.

According to Statistics Finland, the country emitted 48.3 million tons of CO₂ in one year, with agriculture accounting for 13.66% — aligning closely with Gates’ method. However, Finnish author and environmentalist Risto Isomäki, in How Finland Can Halt Climate Change (2019) and Food, Climate and Health (2021), argues that the contribution of animal agriculture to greenhouse gases is severely underestimated. He points out its role in eutrophication — nutrient pollution that degrades lake and marine ecosystems, harming both biodiversity and nearby property values.

Animal farming requires vast resources: water, grains, hay, medicines, and space. Isomäki notes that 80% of agricultural land is devoted to livestock, and most of the crops we grow are fed to animals rather than people. Transport, slaughter, and the distribution of perishable meat further exacerbate the emissions. Official estimates put meat and other animal products at causing around 20% of global emissions, but Isomäki warns the real figure could be higher — particularly when emissions from manure-induced eutrophication are misclassified under energy or natural processes rather than livestock.

Antibiotic Resistance and Zoonotic Pandemics: The Hidden Cost of Meat

A more urgent and potentially deadly consequence of animal agriculture is the emergence of antibiotic-resistant bacteria and new viruses. 80% of all antibiotics produced globally are used in livestock — primarily as preventative treatment against diseases caused by overcrowded, unsanitary conditions. Even in Finland, where preventive use is officially banned, antibiotics are still prescribed on dubious grounds, as journalist Eveliina Lundqvist documents in Secret Diary from Animal Farms (2014).

This misuse of antibiotics accelerates antibiotic resistance, a serious global health threat. Simple surgeries have become riskier due to resistant bacterial infections. During the COVID-19 pandemic, roughly half of the deaths were linked not directly to the virus but to secondary bacterial pneumonia that antibiotics failed to treat. Isomäki (2021) emphasises that without resistance, this death toll might have been drastically lower.

Moreover, the close quarters of industrial animal farming create ideal conditions for viruses to mutate and jump species — including to humans. Early humans, living during the Ice Age, didn’t suffer from flu or measles. It was only after the domestication of animals roughly 10,000 years ago that humanity began facing zoonotic diseases — diseases that spread from animals to humans.

Smallpox, Conquest, and the Pandora’s Box of Domestication

This shift had catastrophic consequences. In the late 15th century, European colonizers possessed an unintended biological advantage: exposure to diseases their target populations had never encountered. Among the most devastating was smallpox, thought to have originated in India or Egypt over 3,000 years ago. Spread through close contact among livestock, it left distinct scars on ancient victims like Pharaoh Ramses V, whose mummy still bears signs of the disease.

When Spanish conquistadors reached the Aztec Empire in 1519, smallpox killed over three million people. Similar destruction followed in the Inca Empire. By 1600, the Indigenous population of the Americas had dropped from an estimated 60 million to just 6 million.

Europe began vaccinating against smallpox in 1796 using the cowpox virus. Still, over 300 million people died globally from smallpox in the 20th century. Finland ended smallpox vaccinations in 1980. I personally received the vaccine as an infant before moving to Nigeria in 1978.

From COVID-19 to Fur Farms: How Modern Exploitation Fuels Pandemics

The SARS-CoV-2 virus might have originated in bats, with an unknown intermediate host — maybe a farmed animal used for meat or fur. China is a major fur exporter, and Finnish fur farmers have reportedly played a role in launching raccoon dog (Nyctereutes procyonoides) farming in China, as noted by Isomäki (2021).

COVID-19 has been shown to transmit from humans to animals, including pets (cats, dogs), zoo animals (lions, tigers), farmed minks, and even gorillas. This highlights how human intervention in wildlife and farming practices can turn animals into vectors of global disease.

Are Our Brains Wired to Ignore Global Crises?

Why do humans act against their environment? Perhaps no one intentionally destroys nature out of malice. No one wants polluted oceans or deforested childhood landscapes. But the path toward genuine, large-scale cooperation is elusive.

The post argues that we are mentally unprepared to grasp systemic, large-scale problems. According to Dunbar’s number, humans can effectively maintain social relationships within groups of 150–200 people — a trait inherited from our village-dwelling ancestors. Our brains evolved to understand relationships like kinship, illness, or betrayal within tight-knit communities — not to comprehend or act on behalf of seven billion people.

This cognitive limitation makes it hard to process elections, policy complexity, or global consensus. As a result, people oversimplify problems, react conservatively, and mistrust systems that exceed their brain’s social bandwidth.

Summary: A Call for Compassionate Comprehension

The destruction of biodiversity, the misuse of antibiotics, the threat of pandemics, and climate change are not isolated crises. They are symptoms of a deeper disconnect between human behavior and ecological reality. While no one wants the Earth to perish, the language and actions needed to protect it remain elusive. Perhaps the real challenge is not just technical, but psychological — demanding that we transcend the mental architecture of a tribal species to envision a truly planetary society.

References

Gates, B. (2021). How to Avoid a Climate Disaster: The Solutions We Have and the Breakthroughs We Need. Alfred A. Knopf.

Isomäki, R. (2019). Miten Suomi pysäyttää ilmastonmuutoksen. Into Kustannus.

Isomäki, R. (2021). Ruoka, ilmasto ja terveys. Into Kustannus.

Lundqvist, E. (2014). Salainen päiväkirja eläintiloilta. Into Kustannus.

Our World In Data. (n.d.). Greenhouse gas emissions by sector. Retrieved from https://ourworldindata.org/emissions-by-sector

Statistics Finland. (n.d.). Greenhouse gas emissions. Retrieved from https://www.stat.fi/index_en.html