The Triple Crisis of Civilisation

“At the time I climbed the mountain or crossed the river, I existed, and the time should exist with me. Since I exist, the time should not pass away. […] The ‘three heads and eight arms’ pass as my ‘sometimes’; they seem to be over there, but they are now.”

— Dōgen

Introduction

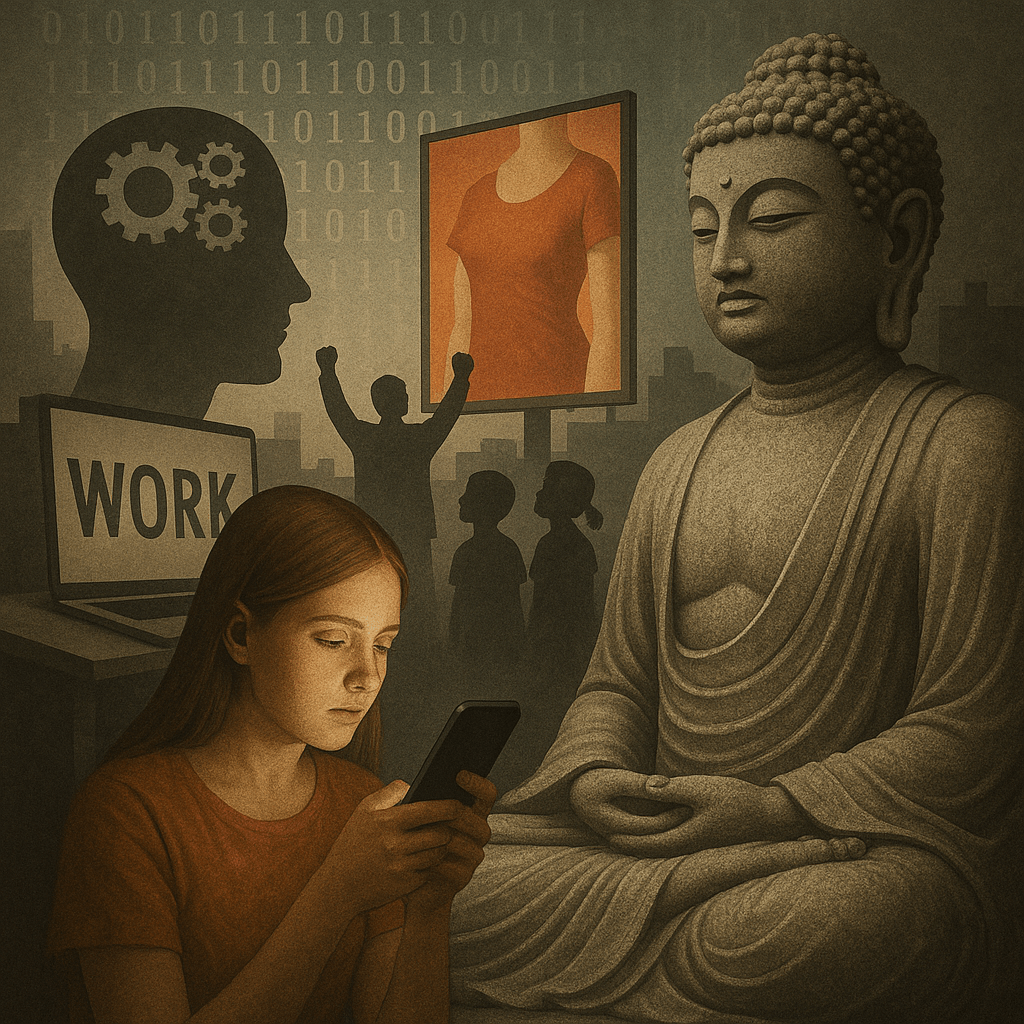

This blog post explores the intertwining of ecology, technology, politics and data collection through the lens of modern civilisation’s crises. It begins with a quote by the Japanese Zen master Dōgen, drawing attention to the temporal nature of human existence. From climate emergency to digital surveillance, from Brexit to barcodes, the post analyses how personal data has become the currency of influence and control.

Originally published in Substack: https://mikkoijas.substack.com/

The climate emergency currently faced by humanity is only one of the pressing concerns regarding the future of civilisation. A large-scale ecological crisis is an even greater problem—one that is also deeply intertwined with social injustice. A third major concern is the rapidly developing situation created by technology, which is also connected to problems related to nature and the environment.

Cracks in the System: Ecology, Injustice, and the Digital Realm

The COVID-19 pandemic revealed new dimensions of human interaction. We are dependent on technology-enabled applications to stay connected to the world through computers and smart devices. At the same time, large tech giants are generating immense profits while all of humanity struggles with unprecedented challenges.

Brexit finally came into effect at the start of 2021. On Epiphany of that same year, angry supporters of Donald Trump stormed the United States Capitol. Both Brexit and Trump are children of the AI era. Using algorithms developed by Cambridge Analytica, the Brexit campaign and Trump’s 2016 presidential campaign were able to identify voters who were unsure of their decisions. These individuals were then targeted via social media with marketing and curated news content to influence their opinions. While the data for this manipulation was gathered online, part of the campaigning also happened offline, as campaign offices knew where undecided voters lived and how to sway them.

I have no idea how much I am being manipulated when browsing content online or spending time on social media. As I move from one website to another, cookies are collected, offering me personalised content and tailored ads. Algorithms working behind websites monitor every click and search term, and AI-based systems form their own opinion of who I am.

Surveillance and the New Marketplace

A statistical analysis algorithm in a 2013 study analysed the likes of 58,000 Facebook users. The algorithm guessed users’ sexual orientation with 88% accuracy, skin colour with 95% accuracy, and political orientation with 85% accuracy. It also guessed with 75% accuracy whether a user was a smoker (Kosinski et al., 2013).

Companies like Google and Meta Platforms—which includes Facebook, Instagram, Messenger, Threads, and WhatsApp—compete for users’ attention and time. Their clients are not individuals like me, but advertisers. These companies operate under an advertising-based revenue model. Individuals like me are the users whose attention and time are being competed for.

Facebook and other similar companies that collect data about users’ behaviour will presumably have a competitive edge in future AI markets. Data is the oil of the future. Steve Lohr, long-time technology journalist at the New York Times, wrote in 2015 that data-driven applications will transform our world and behaviour just as telescopes and microscopes changed our way of observing and measuring the universe. The main difference with data applications is that they will affect every possible field of action. Moreover, they will create entirely new fields that have not previously existed.

In computing, the word ”data” refers to various numbers, letters or images as such, without specific meaning. A data point is an individual unit of information. Generally, any single fact can be considered a data point. In a statistical or analytical context, a data point is derived from a measurement or a study. A data point is often the same as data in singular form.

From Likes to Lives: How Behaviour Becomes Prediction

Decisions and interpretations are created from data points through a variety of processes and methods, enabling individual data points to form applicable information for some purpose. This process is known as data analysis, through which the aim is to derive interesting and comprehensible high-level information and models from collected data, allowing for various useful conclusions to be drawn.

A good example of a data point is a Facebook like. A single like is not much in itself and cannot yet support major interpretations. But if enough people like the same item, even a single like begins to mean something significant. The 2016 United States presidential election brought social media data to the forefront. The British data analytics firm Cambridge Analytica gained access to the profile data of millions of Facebook users.

The data analysts hired by Cambridge Analytica could make highly reliable stereotypical conclusions based on users’ online behaviour. For example, men who liked the cosmetics brand MAC were slightly more likely to be homosexual. One of the best indicators of heterosexuality was liking the hip-hop group Wu-Tang Clan. Followers of Lady Gaga were more likely to be extroverted. Each such data point is too weak to provide a reliable prediction. But when there are tens, hundreds or thousands of data points, reliable predictions about users’ thoughts can be made. Based on 270 likes, social media knows as much about a user as their spouse does.

The collection of data is a problem. Another issue is the indifference of users. A large portion of users claim to be concerned about their privacy, while simultaneously worrying about what others think of them on social platforms that routinely violate their privacy. This contradiction is referred to as the Privacy Paradox. Many people claim to value their privacy, yet are unwilling to pay for alternatives to services like Facebook or Google’s search engine. These platforms operate under an advertising-based revenue model, generating profits by collecting user data to build detailed behavioural profiles. While they do not sell these profiles directly, they monetise them by selling highly targeted access to users through complex ad systems—often to the highest bidder in real-time auctions. This system turns user attention into a commodity, and personal data into a tool of influence.

The Privacy Paradox and the Illusion of Choice

German psychologist Gerd Gigerenzer, who has studied the use of bounded rationality and heuristics in decision-making, writes in his excellent book How to Stay Smart in a Smart World (2022) that targeted ads usually do not even reach consumers, as most people find ads annoying. For example, eBay no longer pays Google for targeted keyword advertising because they found that 99.5% of their customers came to their site outside paid links.

Gigerenzer calculates that Facebook could charge users for its service. Facebook’s ad revenue in 2022 was about €103.04 billion. The platform had approximately 2.95 billion users. So, if each user paid €2.91 per month for using Facebook, their income would match what they currently earn from ads. In fact, they would make significantly more profit because they would no longer need to hire staff to sell ad space, collect user data, or develop new analysis tools for ad targeting.

According to Gigerenzer’s study, 75% of people would prefer that Meta Platforms’ services remain free, despite privacy violations, targeted ads, and related risks. Of those surveyed, 18% would be willing to pay a maximum of €5 per month, 5% would be willing to pay €6–10, and only 2% would be willing to pay more than €10 per month.

But perhaps the question is not about money in the sense that Facebook would forgo ad targeting in exchange for a subscription fee. Perhaps data is being collected for another reason. Perhaps the primary purpose isn’t targeted advertising. Maybe it is just one step toward something more troubling.

From Barcodes to Control Codes: The Birth of Modern Data

But how did we end up here? Today, data is collected everywhere. A good everyday example of our digital world is the barcode. In 1948, Bernard Silver, a technology student in Philadelphia, overheard a local grocery store manager asking his professors whether they could develop a system that would allow purchases to be scanned automatically at checkout. Silver and his friend Norman Joseph Woodland began developing a visual code based on Morse code that could be read with a light-based scanner. Their research only became standardised as the current barcode system in the early 1970s. Barcodes have enabled a new form of logistics and more efficient distribution of products. Products have become data, whose location, packaging date, expiry date, and many other attributes can be tracked and managed by computers in large volumes.

Conclusion

We are living in a certain place in time, as Dōgen described—an existence with a past and a future. Today, that future is increasingly built on data: on clicks, likes, and digital traces left behind.

As ecological, technological, and political threats converge, it is critical that we understand the tools and structures shaping our lives. Data is no longer neutral or static—it has become currency, a lens, and a lever of power.

References

Gigerenzer, G. (2022). How to stay smart in a smart world: Why human intelligence still beats algorithms. Penguin.

Kosinski, M., Stillwell, D., & Graepel, T. (2013). Private traits and attributes are predictable from digital records of human behaviour. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 110(15), 5802–5805. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1218772110

Lohr, S. (2015). Data-ism: The revolution transforming decision making, consumer behavior, and almost everything else. HarperBusiness.

Dōgen / Sōtō Zen Text Project. (2023). Treasury of the True Dharma Eye: Dōgen’s Shōbōgenzō (Vols. I–VII, Annotated trans.). Sōtōshū Shūmuchō, Administrative Headquarters of Sōtō Zen Buddhism.