Humanity’s Legacy of Extinction and Exploitation

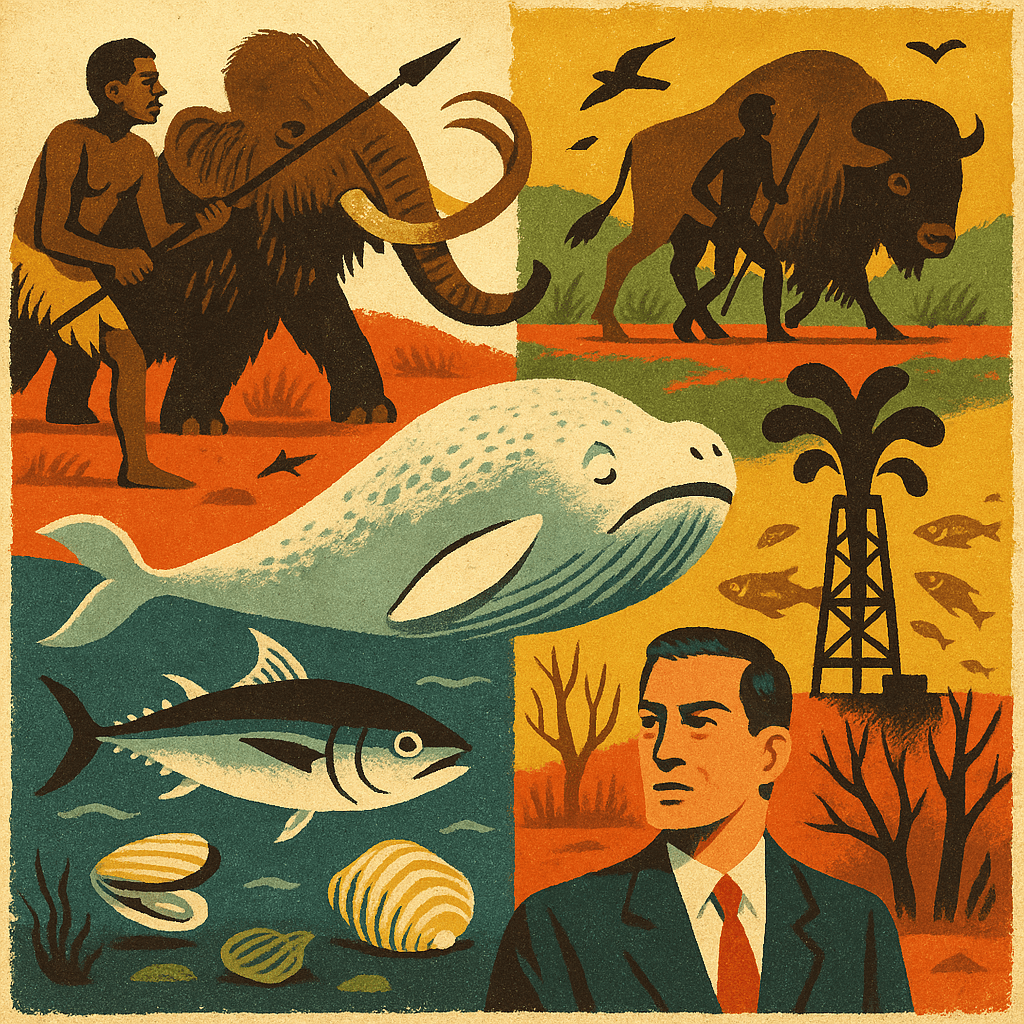

For centuries, human societies—whether ancient hunter-gatherers or modern industrial empires—have played a central role in the extinction of Earth’s largest animals. Although we often romanticise early humans as living in harmony with nature, archaeological and ecological evidence tells a different story. This blog post explores the global impact of Homo sapiens on megafauna, marine ecosystems, and keystone species across continents and millennia, from prehistoric Africa to industrial Japan. It also highlights the ongoing environmental and ethical consequences of our actions.

Originally published in Substack: https://substack.com/@mikkoijas

Humans have consistently driven megafauna to extinction wherever they have migrated. While we may associate the last remaining hunter-gatherers in Africa, Australia, or the Americas with sustainable living, historical patterns suggest otherwise. Wherever Homo sapiens arrived, they rapidly exterminated dangerous predators, large herbivores, and flightless birds.

The Human Legacy of Megafauna Extinction

One striking exception is Africa, where large land mammals have coexisted with humans far longer. This prolonged co-evolution allowed these animals to adapt to human presence. In other parts of the world, some megafauna managed to survive alongside humans—such as various species of bears, moose, deer, and the American bison. Europe’s bison relative, the wisent, nearly went extinct in the 20th century but was saved by zoos.

Even so, ancient hunter-gatherers eventually reached a balance with their prey. Among the San people of the Kalahari, for instance, there’s a known reluctance to hunt declining species. This balance was disrupted by European settlers, leaving San communities today unable to practice their traditions freely.

In North America, indigenous peoples coexisted with the American bison until European settlers deliberately disrupted the balance. Settlers intentionally slaughtered bison to deprive native populations of their primary resource. In the 1700s, 25–30 million bison roamed the plains. By 1880, systematic hunting—sometimes by the U.S. Army—reduced their population to under 100 individuals.

Human impact has extended deep into marine ecosystems. Although coastal communities have fished for thousands of years, their practices rarely led to ecological collapse. According to Curtis Marean, a professor of archaeology at Arizona State University, early Homo sapiens may have survived an extreme ice age (c. 195,000–123,000 years ago) by turning to coastal diets. Marean’s work at Pinnacle Point near Mossel Bay has shown that ancient humans relied on seafood like shellfish and marine mammals. This dietary shift played a crucial role in the survival of early humans during a population bottleneck when their numbers dropped to a few hundred individuals.

Nearby Blombos Cave, studied by archaeologists like Christopher Henshilwood, has yielded the earliest evidence of symbolic thought and advanced tools, including beads and bone-tipped spears.

Although early coastal communities scavenged stranded whales, they did not hunt them at scale. The Romans may have initiated the first industrial whale hunts, particularly off the Gibraltar peninsula, as confirmed by recent findings from Ana Rodrigues’ research team (2018). Later, the Basques became renowned whale hunters, operating from the 1000s to the 1500s across the North Atlantic. By the early 1900s, the North Atlantic right whale population had dropped to about 100. Recent estimates suggest there are only 336 left today.

Tuna, Greed, and the Cold Economics of Extinction

Whales are not the only marine giants hunted to the brink. Species like the bluefin tuna have faced similar pressure. On the Western Atlantic, tuna catches jumped from 1,000 tonnes in 1960 to 18,000 tonnes by 1964—only to collapse by 80% within the same decade. In the Mediterranean, overfishing continued longer but reached catastrophic levels by 1998, leading the IUCN to classify the species as endangered.

The surge in demand came from Japan, where raw tuna is essential for sushi and sashimi. In particular, the fatty underbelly known as otoro became a luxury delicacy in the 1960s. Meanwhile, in the West, tuna was mostly used for cat food.

Today, approximately 80% of all bluefin tuna caught globally is shipped to Japan. The Japanese conglomerate Mitsubishi controls about 40% of the global market, freezing and stockpiling tuna to artificially inflate scarcity and profit margins. Ironically, the Fukushima nuclear disaster compromised these stores when the electricity failed, ruining thousands of tonnes of frozen fish.

From an ecological viewpoint, Mitsubishi’s actions are deeply unethical. From an economic lens, however, they are brutally rational—rarity increases value. As stocks dwindle, prices rise, and shareholders benefit. The more endangered tuna become, the more lucrative they are.

All signs suggest that the oceans are under enormous pressure due to climate change. Seas are warming, acidifying, and absorbing unprecedented levels of carbon dioxide from human activity. In addition, they are polluted and eutrophicated by agriculture and industry.

The Baltic Sea, for example, is the most polluted marine area in the world—thanks in part to the impacts of livestock farming. The same agricultural runoff pollutes Finland’s lakes and rivers.

Ocean ecosystems are remarkably sensitive. A 2°C rise may seem minor—until we compare it to the human body. If your body temperature increased by two degrees and stayed there, you’d die. The sea is no different.

In her book On Fire (2020), journalist Naomi Klein reflects on the 2010 Deepwater Horizon oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico. Operated by Transocean and leased by BP, it remains the largest marine oil spill in history. Witnesses described the ocean as if it were bleeding. Klein recalls being struck by how the oil’s swirling patterns resembled prehistoric cave paintings—one shape even resembled a bird gasping for air, its eyes staring skyward.

Conclusion

From mammoths and bison to whales and tuna, humanity has left a trail of extinction and ecosystem collapse in its wake. Whether through hunting, pollution, or industrial overreach, our actions have irreversibly altered life on Earth. The myth of ancient ecological harmony dissolves under the weight of archaeological evidence and ecological reality. If we are to prevent the next wave of mass extinctions, we must confront the past honestly and reshape our relationship with the natural world—before there is nothing left to save.

References

Henshilwood, C. S. (2002). The Blombos Cave and the origins of symbolic thinking. Science, 295(5558), 1278–1280. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1067575

Hickman, M. (2009). Mitsubishi and the bluefin tuna trade. The Independent. Retrieved from https://www.independent.co.uk

Klein, N. (2020). On Fire: The Burning Case for a Green New Deal. Penguin Books.

Lindsay, J. (2011). Mitsubishi loses tons of tuna after Fukushima power failure. Environmental News Network. Retrieved from https://www.enn.com

Marean, C. W. (2010). When the Sea Saved Humanity. Scientific American, 303(2), 54–61.

Rodrigues, A. et al. (2018). Forgotten whales: Evidence of ancient whaling by the Romans in the Gibraltar region. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 285(1873). https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2018.1088

IUCN. (1998). Bluefin tuna listed as endangered. International Union for Conservation of Nature. https://www.iucn.org